Is Donald Trump Barred from Running for President?

A close look at a very serious argument.

Welcome to the end-of-the-year Jackal. Normally, these are pretty serious and reflective looks at big issues for my readers to munch on over the long holiday break. But this one will very much be in the spirit of a normal Jackal and will break down a complicated argument into terms a normal person with a normal brain can understand. And it also happens to be highly newsworthy right now, with the Colorado Supreme Court kicking Donald Trump off of the 2024 ballot, and Maine following suit. As my friend Alfie the squirrel likes to say: “Let’s get nuts.”

I want to make four points early on:

There is a rule about questions in headlines called “Betteridge’s Law,” which basically says if you ask a question in the headline of your piece the answer to that question is almost always, “No.” This brings me to point two.

I do not think the answer to the question is “No,” but I’m not entirely sure it’s “Yes,” either. I honestly, truly don’t know where I come down on this and I think that’s okay. I go back and forth on it all the time in my mind.

I say that as someone who read, studied, and wrote about this very subject for about three months out of the year. It may make for a lazy headline, but it is still a very serious question, and I think it will ultimately have to be answered by the Supreme Court.

The argument that Trump is disqualified is not spurious, nor is it unconvincing. It is an extremely well-researched argument that was reached in good faith by its principal advocates (dissenters to it, likewise, make good faith arguments), and I think too many people are underestimating the chances that the Supreme Court will affirm Colorado’s decision.

With that out of the way, let’s get into it.

How to disqualify a former president under the 14th Amendment.

Before we get into the actual argument itself, I want to give you some background on where the argument emerged. Shortly after President Trump’s acquittal for the events surrounding January 6th, there was some disappointment over its outcome from both liberals and conservatives. Not only did they see the acquittal as a failure to hold Trump to account, many also saw it as a missed opportunity to bar him from running for president in the future. But some legal experts started to wave their fingers around and say Trump was barred from office anyway, because he had broken the oath he swore on January 20, 2017.

Though they are not the originators of the argument, the movement to bar Trump from running again has been spearheaded by members of the Federalist Society, specifically William Baude (rhymes with “goad”) and Michael Stokes Paulsen. Shortly after Trump announced his candidacy, Baude and Paulsen formally began making the case that he was barred from the Presidency under the 14th Amendment and formalized their argument in a long, written brief this past August.

I want to link to that brief, while providing the other relevant reading materials:

Baude and Paulsen’s brief (which is a pre-print of a law review article coming next year) is here.

Legal scholars Josh Blackman and Seth Barrett Tillman have, without a doubt, the best rebuttal to the argument here.

Former judge J. Michael Luttig and legal scholar Laurence Tribe submitted their own contribution here, and agreed with Baude and Paulsen.

The Colorado Supreme Court’s decision regarding the matter is here, and is maybe the best thing to read out of all three, since it also includes a well-argued dissent.1

You’ll see me cite to my own copies of these materials, where you will also see lots of my own handwritten notes. Bear with me. Fun fact: I discovered a new pen setting on my iPad, so my handwriting transitions from Zodiac Killer to 19th Century poet about midway through each PDF.

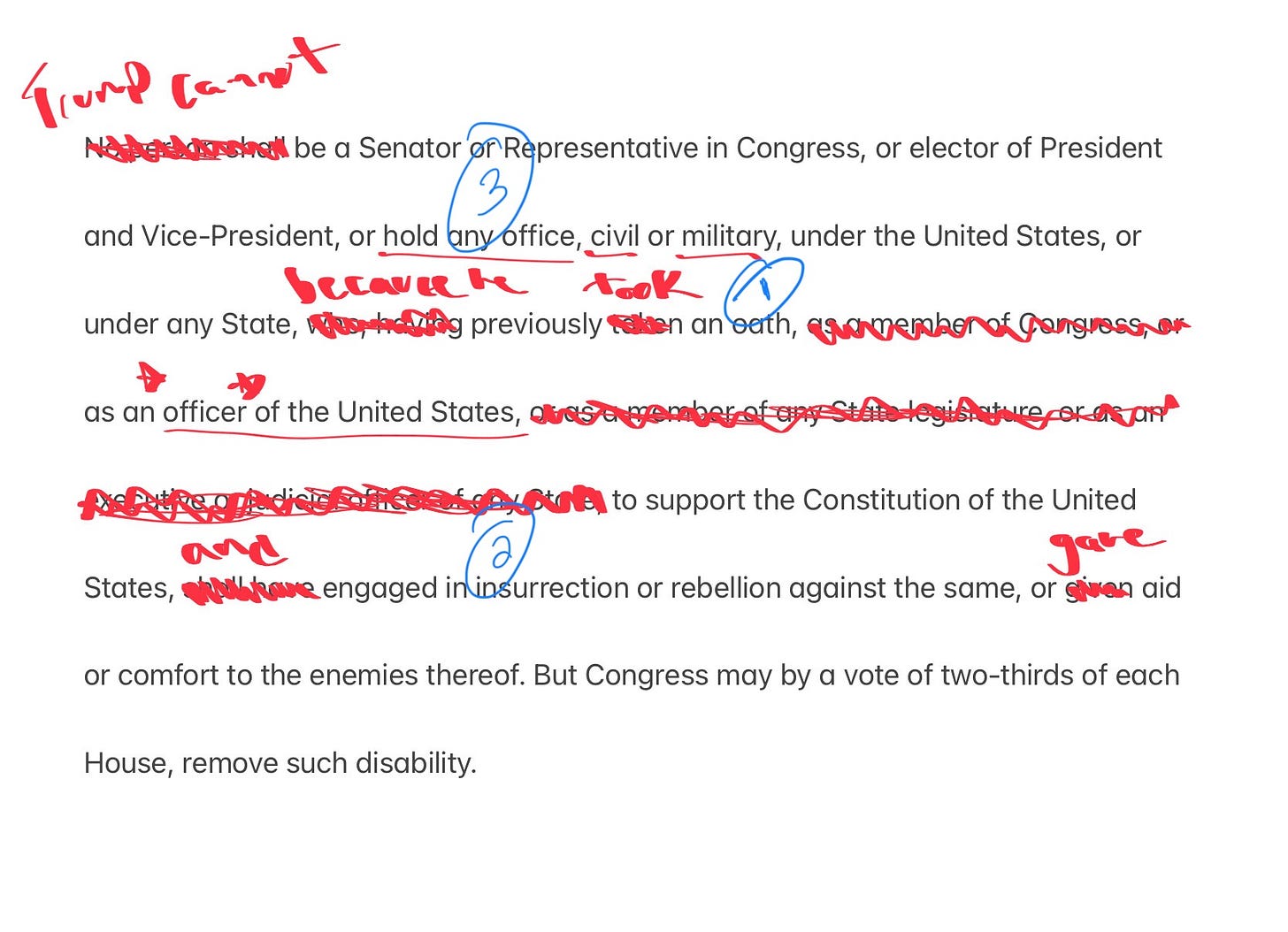

That’s the reading material, so let’s get into exactly what the argument is at its core: Because Donald Trump previously swore an oath to the United States and promised to uphold and protect the Constitution, he violated his oath by engaging in insurrection against the United States when he refused to accept the results of the 2020 Election, culminating in the Capitol riot on January 6th. Because Trump used both his power as President and other illegal means to try and stop the peaceful transfer of power, he is now barred from serving as President again. This is made possible (or is wholly appropriate) according to the 14th Amendment of the United States Constitution, Section 3:

No person shall be a Senator or Representative in Congress, or elector of President and Vice President, or hold any office, civil or military, under the United States, or under any State, who, having previously taken an oath, as a member of Congress, or as an officer of the United States, or as a member of any State legislature, or as an executive or judicial officer of any State, to support the Constitution of the United States, shall have engaged in insurrection or rebellion against the same, or given aid or comfort to the enemies thereof. But Congress may, by a vote of two-thirds of each House, remove such disability.

I made a visual of how this applies to Trump, because that made it easier for me to understand:

When you read it that way, the argument is actually pretty straightforward. But is it actually supported by history? What about the evidence itself? Has this disqualification clause ever been used successfully on anyone else? We’ll get to everything. Or, more realistically, I will try to answer as many questions as I can, and try to address every counter argument when doing so.

Before we do that, I want to give a little history about where this section of the 14th Amendment came from: Just after the Civil War, there was serious concern that a lot of the people who participated in the rebellion would simply return to office and do the same thing again. For obvious reasons, Congress did not want that to happen, so they passed Section 3 of the 14th Amendment.

I don’t want to focus on the history of that too much because it honestly doesn’t matter. The words of the Amendment are still there, and they still apply the same as they did when they were first enacted. In fact, if you read Baude and Paulsen’s brief, they provide great detail about why the Amendment is still active today, and then concede that it is silly for them to do so, because obviously an Amendment that was passed in the 19th Century does not magically stop applying because a certain amount of time has passed.2

That’s the history of the 14th Amendment, but keep in mind that it doesn’t matter all that much (we’ll dive into this more below).

How does Trump’s disqualification…even happen?

I think this is where the Colorado case is the most useful. The actual name of the case is Anderson v. Griswold, named after the first of six voters3 who are suing Colorado’s Secretary of State, Jena Griswold, to try and force her to remove Trump because he is disqualified from serving as President under the 14th Amendment.

Although the District Court in Colorado initially held that Trump - as President - was not a subject of the disqualification clause (more on this later), the judge’s decision was overruled by the Colorado Supreme Court. While their decision has been stayed and Trump has even been restored to the ballot, if their decision goes into effect, Trump will not appear on the ballot in Colorado.

Colorado’s decision is also important in ways that other decisions are not: Because of Colorado’s state laws governing the appearance of Donald Trump on the ballot, they were able to hear about the constitutionality of his appearance. To give an example: Minnesota also heard a challenge to Trump’s disqualification, and ultimately found that because the Minnesota GOP chose their candidate, it was too early for the State to make a formal decision about whether or not Trump could serve as President of the United States.

Colorado has effectively said that because Trump is disqualified from serving as President of the United States, he cannot appear on Colorado’s ballot, period. That is a big deal. If we see the Supreme Court decline to take up the Colorado decision (they are going to take it up), it would be a major indication that they think the decision is correct.

Therefore, if Trump is disqualified under the 14th Amendment, what you are seeing happen in Colorado (and Maine) would begin to happen all over the country: Donald Trump’s name would no longer appear on ballots because he is barred from seeking the Presidency, or any other office.

OK, so break down how he is disqualified.

I think it’s easier to do this by going through a set of factual bullet points:

Donald Trump previously swore an oath to the Constitution on January 20, 2017, when he was sworn in as President.

After the 2020 Election, Trump sought to challenge the results, at first through legal means and then (when those failed) through illegal means.

Trump’s illegal strategy reached its endpoint on January 6th, when the plan was to have Mike Pence reject the electors from the states that had certified Joe Biden as the winner, and to instead select the “alternate slate” of electors Trump’s team had put together from each state.

When Mike Pence failed to comply, Trump incited an angry mob through both his speech that day and through his public statements via Twitter, resulting in the attack on January 6th and delaying the certification of Joe Biden’s victory.

Trump’s illegal actions following the election (up to and including January 6th) are accurately described as an “insurrection,” as Section 3 intends it.

Thus, Trump has violated his oath of office by engaging in insurrection, and is barred from holding any office again, including the Presidency.

Let’s go back to our visual from up above and break it down point-by-point. Follow the blue numbers:

So, Trump:

Took an oath as an officer of the United States.

Engaged in insurrection.

Is now barred from holding any office.

Maybe it seems like I am harping on this too much, but I think this portion is really important to understand, because it will help us address the rebuttals to the argument quickly and clearly.

However, I should say right now that although the legal rebuttals to Trump’s disqualification are really, really not that convincing, it is entirely possible that one of them is correct. Let’s get into them by starting with the best argument for why Section 3 does not apply to Trump.

The President is not an officer of the United States, so Section 3 does not apply to Trump.

Over the past few months I have made this statement to all of the “normies” in my life, and they have looked at me like my head is actually just a shoe with a mouth and two beady little eyes. In fact, while I was out to dinner with a group of friends, one of them asked me about Trump’s disqualification case (then being heard by the District Court, which was big news in humble Denver), and I seriously said out loud, “I think it will eventually get to SCOTUS and they will determine that the President is not an officer of the United States, so the clause doesn’t apply to him.”

It sounds nuts, but there is a long history of legal theory behind it. Here is Josh Blackman, in an article from 20214 (which served as the genesis for two later articles, one of which is linked to above):

[T]here is some good authority to reject the position that Section 3's "officer of the United States"-language extends to the presidency. In United States v. Mouat(1888), Justice Samuel Miller interpreted a statute that used the phrase "officers of the United States." He wrote, "[u]nless a person in the service of the government, therefore, holds his place by virtue of an appointment by the president, or of one of the courts of justice or heads of departments authorized by law to make such an appointment, he is not strictly speaking, an officer of the United States." Justice Miller's opinion, drafted two decades after the Fourteenth Amendment's ratification, is some probative evidence of the original public meaning of Section 3's "officer of the United States"-language. Miller's opinion is some evidence rebutting any presumption of post-1788 linguistic drift with respect to the phrase "officer of the United States." Likewise Mouat rebuts the position that, circa 1868, the obvious, plain, or clear meaning of the phrase "officer of the United States" extended to the presidency.

Blackman’s history is persuasive. There is also a long and detailed recounting of this position compiled by the Volokh Conspiracy (where Blackman often writes), and it is a good faith interpretation of the Constitution.

However, if that’s Trump’s out here, why didn’t any of the dissents in the Colorado case mention it? I honestly think it’s because when you read the District Court’s decision out loud, it just sounds ludicrous.5 In fact, Trump’s own attorneys stated plainly in their briefs that “of course” the President is an officer of the United States, probably because the alternative comes off as nutty.

Under Blackman’s interpretation, if a Senator Lindsey Graham had engaged in Trump’s behavior, he would be barred from holding any office, but because Trump was the President at the time, he gets a freebie.

Baude and Paulsen use a traditional textualist approach, which is to say that the Constitution does not include a “secret code” that requires a Legend to interpret it. The words should mean what they purport to mean, and to a normal and plain person (both in the 21st and the 19th Century), the President is an officer of the United States.

The Colorado Supreme Court basically said the same thing:

When interpreting the Constitution, we prefer a phrase’s normal and ordinary usage over “secret or technical meanings that would not have been known to ordinary citizens in the founding generation.” District of Columbia v. Heller, 554 U.S. 570, 577 (2008). Dictionaries from the time of the Fourteenth Amendment’s ratification define “office” as a “particular duty, charge or trust conferred by public authority and for a public purpose,” that is “undertaken by…authority from government or those who administer it.” […] The Presidency falls comfortably within these definitions.

They continued (and here you can see my ugly notes):

Even leaving all of this aside, there is history from Congress that the language was intended to apply to the Presidency. As Baude and Paulsen detail, we have the actual conversations from Senators on the floor of the Senate preserved for us to read. One Senator - Reverdy Johnson - explicitly said that the proposed amendment “does not go far enough,” because a Confederate “may be elected President or Vice President of the United States.” Johnson asked, “[W]hy did you omit to exclude them? I do not understand them to be excluded from the privilege of holding the two highest offices in the gift of the nation.”

Then, he got his response from Senator Lot Morrill: “Let me call the Senator’s attention to the words ‘or any office, civil or military, under the United States.” Johnson basically then said, “Ah, I got it. The Presidency is included.”

In other words, it doesn’t really matter whether or not the President is an officer or not, the intent of the 14th Amendment is clear: If you engage in insurrection, you cannot serve as President of the United States. Period. The Colorado Supreme Court repeatedly points out that there was a serious worry that Jefferson Davis would run for president, and Section 3 addressed those concerns.

All that said, citing to legislative (and even normal) history is a slippery slope. What if Senators Morrill and Johnson took a trip to the bathroom together later on, hashed it out, and then both said, in unison with their hands clasped, “The President is not an officer of the United States, and we are big dumb idiots for thinking otherwise?” We don’t have a recording of that conversation, and that’s why textualists are skeptical of arguments from “legislative history.” However, I think in an instance such as this, where the language is so muddled and unclear, it is a useful tool. In any case, the argument that Section 3 applies to the President, or that it was intended to, is pretty persuasive.

OK, but Trump did not engage in insurrection.

Any left-wing person reading this subheading will probably think this section will be short, but it is likewise true that a Trump supporter believes it at their core. So, let’s get our definitions straight.

Off the bat, I think it’s important to state that “insurrection” is actually less scary than it sounds. Although the 14th Amendment says “insurrection or rebellion” is enough to get you yeeted from office, rebellion is far, far worse. In fact, Abraham Lincoln himself said that a rebellion had to be defined as a “giant insurrection,” so it logically follows that an insurrection is a “little rebellion.” In the words of George Bluth, Sr., it is just some “light treason,” but not a full-scale establishment of the Confederate States of America. In the same way that all bourbon is whiskey, but not all whiskey is bourbon, all rebels are insurrectionists, but not all insurrectionists are rebels.

Speaking of whiskey, that brings me to our sponsor, “The Whiskey Rebellion.” It is seriously one of my favorite little moments in American history (not just because it involves whiskey) and it is instructive here. Although we call it the “Whiskey Rebellion,” it was called the “Whiskey Insurrection” in the late 18th Century. And that makes sense, because while it was a big conflict in our young nation, the casualties were few and the consequences were muted. It is somewhat analogous to January 6th, which was probably not a rebellion, but it was certainly a violent insurrection against government.

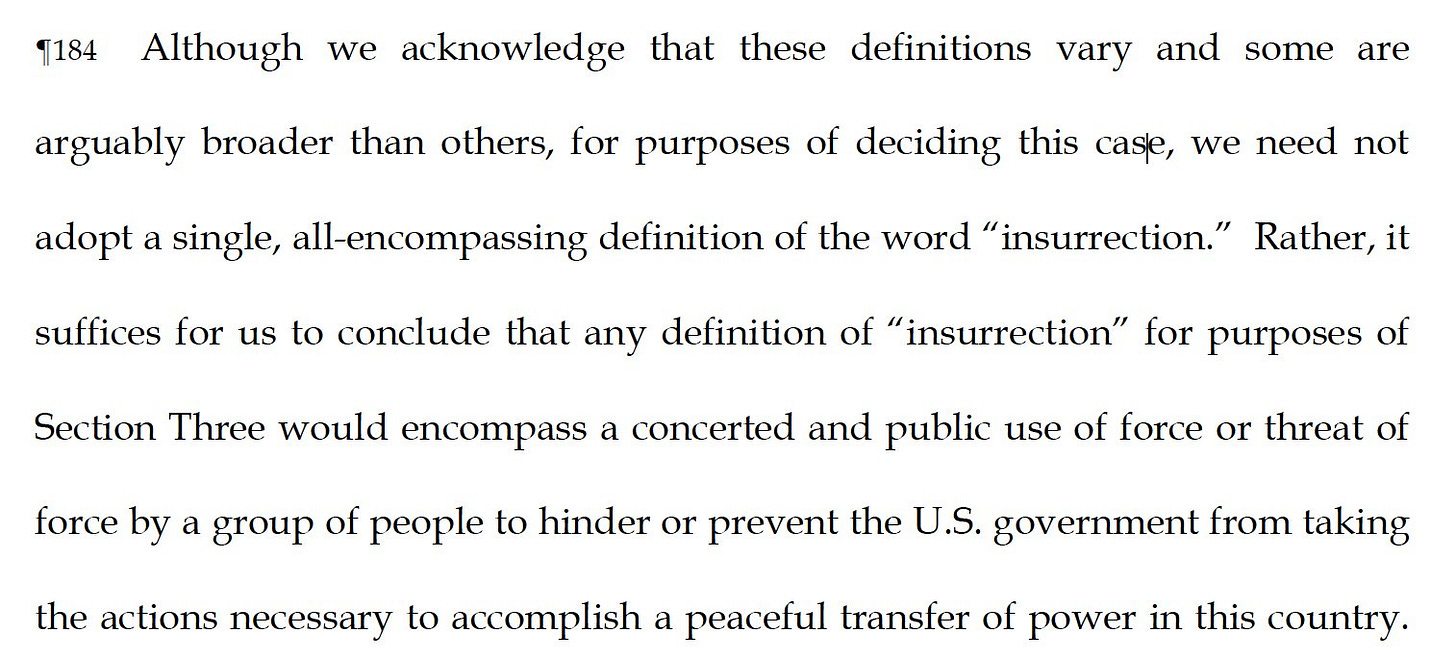

With those parameters set, a plain interpretation of the word “insurrection” fits Trump’s actions. Webster defines insurrection as, “An act or instance of revolting against civil authority or an established government.” It is hard to make the case that Trump did not engage in that activity, as opposed to the opposite. After the election was certified, Trump took multiple avenues to try and challenge the results, and when those failed, he resorted to illegal means, e.g., the fake electors. And when the illegal means failed, January 6th happened. Here is Colorado’s Supreme Court:

As our detailed recitation of the evidence shows, President Trump did not merely incite the insurrection. Even when the siege on the Capitol was fully underway, he continued to support it by repeatedly demanding that Vice President Pence refuse to perform his constitutional duty and by calling Senators to persuade them to stop the counting of electoral votes. These actions constituted overt, voluntary, and direct participation in the insurrection. Moreover, the record amply demonstrates that President Trump fully intended to—and did—aid or further the insurrectionists’ common unlawful purpose of preventing the peaceful transfer of power in this country. He exhorted them to fight to prevent the certification of the 2020 presidential election. He personally took action to try to stop the certification. And for many hours, he and his supporters succeeded in halting that process.

They later go into more detail:

I’ll go even further than they did, and include these lines from Trump’s speech that day:

Our country has had enough. We will not take it anymore, and that is what this is all about. And to use a favorite term that all of you people really came up with, we will stop the steal.

And I would love to have if those tens of thousands of people would be allowed the military, the Secret Service and we want to thank you and the police and law enforcement great you're doing a great job, but I would love it if they could be allowed to come up with us. Is that possible?

The weak Republicans--and that's it, I really believe it. I think I'm going to use the term. The weak Republicans. You've got a lot of them and you've got a lot of great ones. But you've got a lot of weak ones. They've turned a blind eye.

And Mike Pence is going to have to come through for us. And if he doesn't, that will be a sad day for our country because you're sworn to uphold our constitution.

Now it is up to Congress to confront this egregious assault on our democracy. And after this, we're going to walk down and I'll be there with you. We're going to walk down--

We're going to walk down. Anyone you want, but I think right here, we're going to walk down to the Capitol--Because you'll never take back our country with weakness. You have to show strength and you have to be strong.

We have come to demand that Congress do the right thing and only count the electors who have been lawfully slated. Lawfully slated.

Trump - who was fully aware that there were people in the crowd armed with weapons - pushed his followers to violence and then allowed the attack to go on for hours, outright refusing to send in the National Guard, even after aides (including his own children) pleaded with him. While that was going on, he was actively pushing Pence to reject Biden’s win.

Both the Colorado Supreme Court and the District Court determined that Trump engaged in insurrection, and the latter did so after a full hearing on the evidence, with rebuttals from Trump’s attorneys. But here is the thing: Although I think Trump engaged in insurrection, it doesn’t really matter, because he quite literally gave “aid” to those who did.

It has slipped under the radar, but January 6th is officially an insurrection. Stuart Rhodes, Enrique Tarrio, and others were all convicted of “seditious conspiracy,” which is the sedition statute. That states:

If two or more persons in any State or Territory, or in any place subject to the jurisdiction of the United States, conspire to overthrow, put down, or to destroy by force the Government of the United States, or to levy war against them, or to oppose by force the authority thereof, or by force to prevent, hinder, or delay the execution of any law of the United States, or by force to seize, take, or possess any property of the United States contrary to the authority thereof, they shall each be fined under this title or imprisoned not more than twenty years, or both.

This statute actually has a long history. When you look at some of the earlier versions of United States Federal Code, it was grouped in with “inciting rebellion or insurrection.”

Baude and Paulsen also note that “sedition” is the singular version of insurrection:

And in defining insurrection, Webster noted that insurrection is “equivalent to sedition, except that sedition expresses a less extensive rising of citizens.” This suggests a spectrum from sedition (not covered by Section Three) to insurrection to rebellion (both covered).

If various members of the crowd on January 6th officially engaged in sedition, thus making their collective action an insurrection, then it is undeniable that Trump gave aid and comfort to them by his unwillingness to do anything to stop the attack.

This isn’t some “secret code” that is lying there within the statute; this is factually what it says, and it is factually what happened that day. Again, the Colorado Supreme Court says we don’t have to play games:

Trump engaged in insurrection, and it is notable that none of the dissenting judges on Colorado’s Supreme Court contested that fact. There is also another wrinkle here: Section 3 of the 14th Amendment is currently barring public officials from office, and resulted in Couy Griffin being removed from his post as Commissioner of Otero County, New Mexico. If Section 3 and all of its factual criteria applies to him, how can it not apply to Trump?

A bipartisan Congressional Committee similarly determined that Trump engaged in insurrection, and it is a tall order to ask any justice to make such an argument. A final Trump tweet from that day drives the point home:

“These are the things that happen.” It was an insurrection.

OK, but Trump hasn’t been convicted of engaging in insurrection, which is required.

This is probably the second-best argument against Trump’s disqualification, and it is the one dissenting Justice Carlos Samour latched onto in the Colorado case. Baude and Paulsen - along with the Colorado Supreme Court - determine that Section 3 of the 14th Amendment is “self-executing,” which means it exists in an active form without further action needed from Congress or anyone else.

Samour found this to be a tough pill to swallow, and he cited to Section 5 of the 14th Amendment, which grants Congress the power to enforce the provisions of the 14th Amendment:

Although Section Three was included in Powell among the so-called Qualification Clauses, closer scrutiny reveals that it is unique and deserving of different treatment. That’s because Section Three is the only one that is “qualifie[d]” by the following language: “[C]ongress shall have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provision[s] of this article.” Griffin’s Case, 11 F. Cas. at 26 (emphasis added) (quoting U.S. Const. amend. XIV, § 5 and stating that “[t]he fifth section qualifies the third”). None of the other Qualification Clauses—even when viewed in the context of the original Articles in toto—contains the “appropriate legislation” modifier. Indeed, that modifier only appears in certain other Amendments, none of which are objectively relevant to the instant matter. I need not contemplate what bearing, if any, this has on the self-executing nature of constitutional provisions more generally. While that might be an open question, see Blackman & Tillman, supra (manuscript at 23) (noting that there appears to be “no deep well of consensus that constitutional provisions are automatically self- executing or even presumptively self-executing”), the demands of the instant matter counsel in favor of limiting my exposition to the Constitution’s presidential qualifications, especially those found in Article II, Section One, Clause Five.

Samour essentially says that without an official determination by Congress, or a conviction (even a bench trial), then it cannot be determined that Trump engaged in insurrection for the purposes of disqualification. This is a tempting argument, and it might be an escape-hatch that the Supreme Court justices attempt to use, but it is still weak. Samour latches on to Section 5 of the 14th Amendment, which says:

The Congress shall have the power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions of this article.

He treats Section 5 as if it only applies to Section 3, but if it does, then it has to apply to the entire Amendment. That means other portions of the 14th Amendment that are plainly self-executing, like, “…nor shall any State deprive any person of life, liberty, or property, without due process of law,” would need to be enforced by Congress.

No one believes that, because it doesn’t make sense. Moreover, the plain history of Section 3’s enforcement shows that no legal determination was required for it to apply. In fact, after the Civil War, the overwhelming majority of people (and possibly all of them) who were barred from office were not convicted of insurrection or rebellion first. Adding a requirement that Trump be convicted or that Congress should determine his guilt reads something into the text that plainly isn’t there, and it strikes me as dangerous. What happens if the Supreme Court adopts this argument, and then charges are brought against Trump for insurrection? What if it’s not even Jack Smith who brings them, but a random prosecutor somewhere in the country?

That actually feels more messy to me than simply reading the actual text of the Amendment, but it is not a weak argument. And it is reasonable to say that many Americans would want to see some sort of formal conclusion about Trump’s “engagement in” insurrection before seeing Section 3 apply to him.

The argument may be legally tight, but it still feels wrong.

I actually think this section is more important than many people assume. To get the easy stuff out of the way, I think there are bad arguments against the decision that can be grouped in here. For example, many Trump supporters are saying that if Maine and Colorado can bar Trump from the ballot, then Texas can bar Joe Biden from their ballot, and cite to something like “the border” as an example of “insurrection” that should be applied.

This is akin to saying you are going to sue your own dog for defecating on your couch. You can file such a lawsuit, but a judge is going to dismiss it (and maybe yell at you). There is no plausible argument that says the Biden Administration’s immigration policy is an “insurrection” (even leaving aside the fact that they have deported 3.5 times more immigrants than the Trump Administration) because it is not an active resistance against government

But I think there are a lot of different reasons to oppose Trump’s disqualification from the ballot that do not involve legal reasoning or the retaliatory effects. For instance, many of Trump’s supporters say this argument is “un-democratic,” which is undeniably true. The counter argument is that many of the Constitution’s requirements for office are “un-democratic,” such as being 35 before running for President, or being a natural-born citizen, or being limited to only two terms. That’s fair, but it doesn’t rebut the point.

There is also a mechanism within Section 3 itself that allows for a democratic solution: By a two-thirds majority, Congress can remove Trump’s disqualification by a vote. If Trump’s supporters want him to be eligible again, they can simply win more elections (which is often the answer to most of the problems people have with our system). But that still feels like a tall ask.

Baude and Paulsen concede that Section 3 is harsh and bold. It is a serious punishment after concluding that one has committed a serious offense. But it is also just as plainly true that the best way to suck the Trump poison out of our polity is to watch him lose two elections, fair and square.

Baude and Paulsen also seem indifferent to the real potential for violence from Trump supporters, who will inevitably see this as an attack on their candidate from a system they view has hopelessly corrupt (mostly thanks to Trump’s deception).

They argue that those considerations shouldn’t matter, and only the text and original intent of the Constitution should be weighed. Throughout their piece, they repeatedly make arguments from both textualist and originalist grounds (two distinct but adjacent political philosophies) in ways that are clearly meant to appeal to the more conservative members of the Supreme Court.

Textualists like Justice Gorsuch and originalists like Justice Alito might find such arguments difficult to dismiss, but as someone who is neither an originalist nor a textualist, I think it’s fair for me to say this: An argument to do something this explosive has to be 100% correct and airtight. Although I think Baude and Paulsen (and the Colorado Supreme Court) have laid out a detailed and convincing case, I don’t know if I can call it airtight. Maybe I’m holding onto something emotionally that I shouldn’t, or maybe I am understanding the law poorly. But it feels incomplete, even if it is hard to argue against.

I’m also practical in ways that Baude and Paulsen are not, because they have scruples. Right now, Trump is facing 91 felony counts in multiple jurisdictions, and it seems likely that he will be on trial in early March or shortly thereafter for his role in January 6th. I’ve said this many times, but prosecutors have an 82% success rate in securing convictions if a defendant doesn’t take a plea agreement. A conviction of Trump by a jury of his peers also feels cleaner than a disqualification under the 14th Amendment, so maybe we can punt on the latter.

Whatever happens, the Supreme Court is going to have the final say, and I am ultimately worried about the reaction to their decision, whichever way it goes. If they determine that Trump is disqualified under Section 3, his supporters will go nuts. If the Court decides that Section 3 does not apply to Trump, liberals will blame it on a conservative-leaning Supreme Court which has three justices appointed by Trump himself.

The system we have dictates that SCOTUS resolves conflicts in Constitutional interpretation. They do not have an army to enforce their decisions and instead have to rely on the Executive branch to carry out any enforcement. The resolution of the decision will require a buy-in from everyone else, with ongoing respect for the Supreme Court as an institution. You will not catch me saying otherwise in this space (though I may have some criticisms of SCOTUS’s decision, should it come).

That is the system that we have and it is worth preserving. And if it is able to beat back Trump - who very candidly wants to tear the system down - then it feels almost poetic if it sends him off into a bright, Floridian sunset.

I hope you all have a great New Year and have enjoyed Christmas and the holidays. The Jackal returns to full speed in January.

The Colorado Supreme Court’s official vote tally was 4-3, but two of the three dissenters focused on more technical issues, and only one really addressed the merits of the decision. I focus on that dissent in this piece.

They also spend time addressing an argument that I don’t think is that serious, which is that Congress granting amnesty in 1872 to participants in the Civil War essentially nullified the clause. If Congress can simply toss out parts of the Constitution that they don’t like, that would be a novel a new concept in American legal theory.

There are lots of notes in news stories about how these were mostly Republican voters, but we are all grownups here; this was a test case, and the people who are suing are “Republicans” in the same way [insert Never Trump Republican name here] is a Republican.

It’s worth noting that this article essentially addresses whether or not Trump’s actions on January 6th warranted disqualification under the 14th Amendment, and it’s from January 20, 2021, just showing you how long this debate has been going on.

It goes without saying, but just because something sounds ludicrous, doesn’t mean it is unconstitutional, see: The outcome of Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission.