Critical Race Theory is the New Sharia Law (Part One)

Conservatives don't know what it is, but they sure do hate it anyway.

I’m going to be totally honest with all my beautiful babies: I take pride in my ability to distill complex topics into something that is digestible to just about anyone. Early on in “my career,” I gave a letter I had written to an attorney for editing. It was a response to a judge who had written us, so I tried to be professional and smart. He handed it back to me and said, “Great job. Now write it like you were writing a letter to your Mother.” Lose the big words. Write as clearly as possible. Don’t confuse your reader. It was the best advice I’d ever gotten.

Therefore, I went into this newsletter thinking that I’d be able to break down this insanely complex legal topic that has been in existence for 50 years in just a quick email. But I went to Elisabeth, told her I was at about 2,000 words and still not finished. She then persuaded me to do an audible and make it two separate parts. So, now I can quite literally say that if you think that’s a great idea you can thank Elisabeth, and if it makes you mad you can put every ounce of blame on her.

In light of the foregoing, this post comes with a warning: It is long and it will only be on the Title’s subject. There is way too much info here to give you any other distractions. Don’t feel bad if you don’t read the entire thing in one sitting on a Monday morning. Take your time, come back to it, and also (please please please) read the stuff I link to, of which there is a lot. I’ll hit you with Part Two after the Fourth.

In the grand, pre-Trump days of 2014, Alabamans successfully passed “Amendment One,” which banned Sharia Law1 - a set of religious laws practiced by Muslims - from being used in Alabama’s courts. While this may or may not have been upsetting to the Muslim2 who lived in Alabama, it was widely considered to be an unnecessary, late entry into the anti-Sharia Law craze that happened from about 2008-2012. If you are thinking that those dates just so happened to coincide with the Presidency of a certain African-American who many on the Right suspected was a secret Muslim, then you know where I’m about to go with Critical Race Theory (CRT). Here’s a fun look at who was interested in Sharia Law during that time:

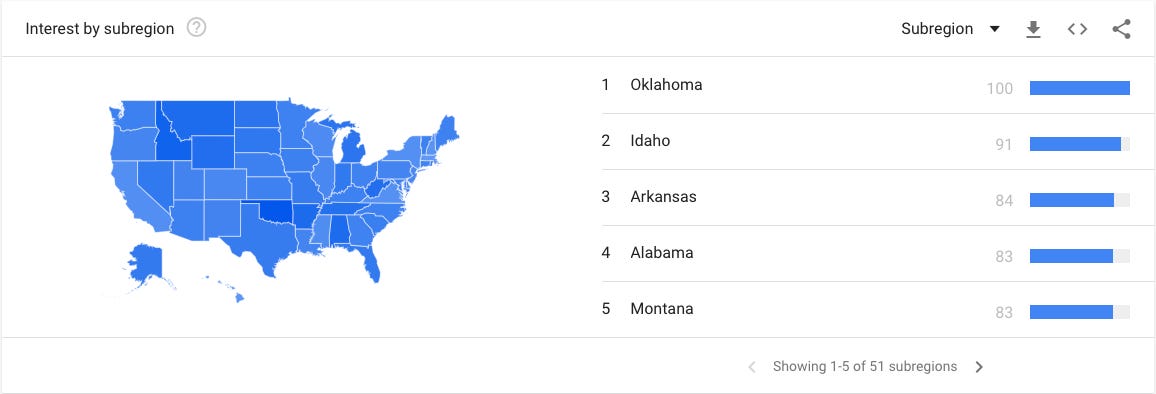

Here are the five states that were the most interested in CRT, from about 2004 to the present:

I think the comparison between the two is instructive, because it’s all from places where both Sharia Law and CRT are not actually real things. One phrase was on the lips of every conservative in the early days of Barack Obama’s Presidency, and the other is currently being discussed ad nauseam on Fox News, which is currently the main forum for discussion of conservative ideas, intellectual or otherwise. At its core, the Right’s current campaign against CRT is about making sure conservatives stay angry and hoping that anger lasts until about November of 2022.

The reason I am being so cynical about critiques of CRT is that one of its main proponents has told me that I should be; Christopher Rufo, who is a major conservative activist against CRT, openly admitted that his campaign is being waged in bad faith:

And, if you think that tweet is him speaking out of context, he doubled down on it in an interview with The Washington Post. He said:

If you want to see public policy outcomes you have to run a public persuasion campaign…I basically took that body of criticism, I paired it with breaking news stories that were shocking and explicit and horrifying, and made it political. Turned it into a salient political issue with a clear villain (my emphasis).

Very rarely do you have someone blatantly giving up the game in public, but in this case Rufo is doing just that. He is admitting that he took “that body of criticism” (CRT) and applied it to “breaking news stories,” that he (notably) does not even argue are related to CRT. So, if you are wondering why all of your relatives are discussing CRT at the kitchen table, it’s because of an Italian-American Trump voter from Washington (and, as the Washington Post piece highlights, President Trump saw Rufo on Fox News and thus made being anti-CRT a thing in the Republican Party). Now that we know why we’re discussing CRT, we should probably figure out what it is.

What is Critical Race Theory?

If you want to start with how CRT should be defined, I think it’s best to start with the C and T of that acronym. Critical theory is an academic discipline which teaches “that social problems are influenced and created more by societal structures and cultural assumptions than by individual and psychological factors.” The parts I bolded there are important, because they both get to the heart of CRT.

CRT, which first arose in the 1970s and 1980s, basically teaches that because social structures and culture assumptions about race are ingrained in the American experiment, even the country’s attempts to enact laws that are facially neutral can have (unintended, but still) racist outcomes. Supreme Court Justice Brett Kavanaugh actually made this argument (intended or not) in his recent decision striking down the NCAA’s restrictions on “compensation” for college athletes:

The bottom line is that the NCAA and its member colleges are suppressing the pay of student athletes who collectively generate billions of dollars in revenues for colleges every year. Those enormous sums of money flow to seem- ingly everyone except the student athletes. College presi- dents, athletic directors, coaches, conference commission- ers, and NCAA executives take in six- and seven-figure salaries. Colleges build lavish new facilities. But the student athletes who generate the revenues, many of whom are African American and from lower-income backgrounds, end up with little or nothing (my emphasis).

This is basically CRT at its core: Because there are social structures that have been propped up by racism for so long, it will take more than color-blind, neutral application of the law to make any corrections.

There have been a lot of jokes made about how Republicans cannot define CRT when they are asked what it means. But the theory itself, when it is defined in its purest forms, is almost entirely benign. Who can argue that there are still patterns of inequality in America, and that some of those patterns are tied to institutional or systemic racism?

I can give a pretty good and personal example. A recent Bloomberg op-ed presented a fix to end the racial gap in home ownership:

Beginning in the 1930s, government-subsidized mortgages enabled people to buy homes, invest in communities and build equity — wealth that they then passed on to their children. But the benefits were limited by race. Between 1934 and 1968, 98% of loans insured by the Federal Housing Administration went to White people. The presence of a single Black family in a new subdivision was enough for the FHA to refuse financing. The result was residential segregation and a legacy of entrenched disadvantage. […] It’s time for a different approach. Instead of encouraging homeowners to take on debt they can’t afford, give them equity by providing down payment assistance.

Although this op-ed is from June 23rd, its applicability goes back a long time. You see, since its first advent in the 1970s, CRT found an unlikely ally in libertarian circles, since it gets at the heart of libertarian thought: Government is generally sucky. However, because libertarians tend to be on the Right and race theorists tend to be on the Left, it was the libertarians who put a heavier focus on how government was behind a lot of the segregation that permeated throughout the U.S. in the 20th Century. And although a lot of that had to do with individual states, Richard Rothstein focused on how it was related to federal policy. In his book The Color of Law, Rothstein tells the story of Vince Mereday, a black World War II veteran who was looking to buy a home on Long Island. He ran into trouble, because the town he wanted to buy in (and helped build) did not allow blacks to move in:

By the time the federal government decided finally to allow African Americans into the suburbs, the window of opportunity for an integrated nation had closed. In 1948, for example, Levittown homes sold for about $8,000, or about $75,000 in today’s dollars. Now, properties in Levittown without major remodeling sell for $350,000 and up. White working-class families who bought those homes in 1948 have gained, over three generations, more than $200,000 in wealth. […] Mereday, who helped build Levittown but was prohibited from living there, bought a home in the nearby, almost all-black suburb Lakeview. It remans 74 percent African American today. […] Although white suburban borrowers could obtain VA mortgages with no down payments, Vince Mereday could not because he was African American.3

Lakeview is only a couple towns over from Valley Stream, which is where my parents settled our family after we moved out of Queens. Rothstein notes that homes in Lakeview today “currently sell for $90,000 to $120,000,” meaning that the Mereday family gained, at most, “$45,000 in equity appreciation over three generations, perhaps 20 percent of the wealth gained by white veterans in Levittown.”

As government policies shuffled white people into “white neighborhoods” and black people into “black neighborhoods,” the actual people learned from those policies with their own eyes, and then applied what they had learned. Even though the town next to Lakeview (Malverne) has a lower median household income, Lakeview has been routinely ignored by Nassau County, whereas Malverne has received a myriad of benefits. It’s a story that plays out pretty regularly on Long Island and its residue is still present. In November of 2019, Long Island’s biggest newspaper, Newsday, published the results of a three-year investigation into the disparate treatment of minorities by real estate agents:

In fully 40 percent of the tests, evidence suggested that brokers subjected minority testers to disparate treatment when compared with white testers with inequalities rising to almost half the time for black potential buyers. Black testers experienced disparate treatment 49 percent of the time – compared with 39 percent for Hispanic and 19 percent for Asian testers. In seven of Newsday’s tests – 8 percent of the total – agents accommodated white testers while imposing more stringent conditions on minorities that amounted to the denial of equal service between testers (my emphasis).

Although Rothstein highlighted government’s failures in housing policy, those failures have created a trickle-down effect that has now infected private businesses. To me, the word systemic (“fundamental to a predominant social, economic, or political practice”) isn’t really the way to describe this; this is more endemic, because it is a “disease” that is “regularly found;” like the flu, it keeps popping up year after year. What’s notable is that this wasn’t in-your-face, drawing racist graffiti on a black neighbor’s house telling them to leave the neighborhood on Martin Luther King, Jr., Day (that literally happened across the street from us and my Dad got to talk to the newspaper about it). Instead, this was much more insidious. As the Newsday piece notes, “This is something that didn’t happen in the Deep South…it happened in one of the most educated, most liberal regions of the country.”

Kimberlé Crenshaw - the academic who literally coined the term Critical Race Theory - has described CRT as, “Not so much a thing, but a way of looking at a thing,” and that by changing the way Americans looked at law and how it might not be the “neutral referee” that we want it to be, we could “do better with the promises that are embedded in the Constitution.” Almost like we should strive for a “more perfect Union,” or something like that.

The fundamental point here is that because actual racism was a part of American policy for the better part of the country’s history, its residue and latent effects did not magically disappear on the day Lyndon B. Johnson signed the 1964 Civil Rights Act. In fact, CRT arose in the 1970s precisely because the Civil Rights Act was not explaining why minorities were still experiencing disparate outcomes even after its passage. For shit’s sake: My parents still live a few blocks down from Lindner Place in Malverne, a street that is currently named after a Ku Klux Klan leader. If you think we magically pulled every element of racism out of American society, I have an incredible investment opportunity in Brooklyn for you.

This feels like a good place to end Part One, right? In Part Two, I’ll get into the parts of CRT that are less good, like Robin DeAngelo and Ibram X. Kendi, who get criticism from not only anti-CRT people but also pro-CRT people, mostly because neither of them are actual CRT people (people).

Have a great Fourth of July. We will be in Michigan and will try to include some pics for you in Part Two.

The pic this week is from my friend Brian, who is cruising across Colorado (and then later the U.S.) with his family. You can find them on Instagram at: SmallSpaceBigAdventure.

My entire inspiration for using Sharia comes from Radley Balko on Twitter. He made a comment about it that I can’t find, and I thought it was a great comparison. Since I can’t find it, I’ll link to his Twitter but just know that the Sharia comparison didn’t come from me.

Intentional.

If you are currently trying to buy a home anywhere in Denver or in New York, you have permission from GOD HIMSELF to laugh at these prices. Rothstein’s book was written in 2017.